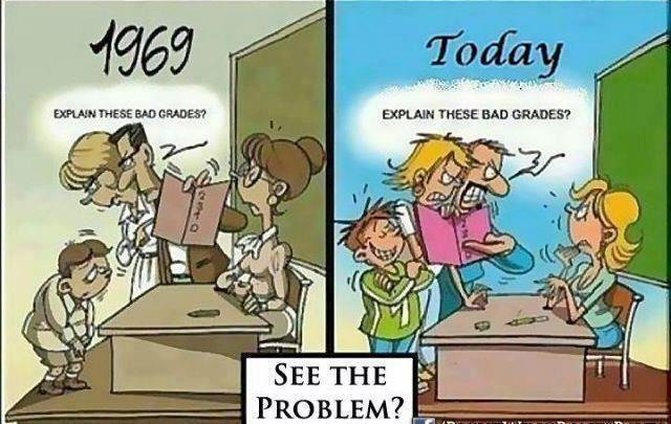

To my students: I can help you better at the beginning of the semester than at the end. Talk to me.4/15/2017  At the end of each semester, there is a buzz around post-secondary campuses – a palpable tension among students and faculty alike. Students are stressed out about grades, final papers and assignments. Faculty are stressed out about marking, fielding student excuses and complaints, and employment politics. What results is less compassion from both sides, and more whining, complaining, and actions which only serve to exacerbate the problem. In my developmental psychology class, we discuss what makes one generation different from the one before - how generation-based variables affect our development. A generation ago, students wouldn’t dare challenge their professors over grades. You got what you got. Going into your professor’s office to complain just didn’t happen. Of course, now, it’s much easier to send an email – you don’t need to stand face to face with your professor and question his/her judgement and ability to grade. Technology as such is one thing that makes millennials, as a generation, different. It also forms the basis of many late assignment excuses – the assignment didn’t save, wouldn’t upload, wouldn’t print, etc. Finances are also different. The cost of rising tuition, and expectations of grad school versus work after graduation increase stress and necessitate many students still living (and being taken care of) in their parents’ homes. There are certainly some upstream causes within the school system. The push for standardized testing and meeting minimum statistical standards causes teachers to focus on the importance of the difference between 69% and 70%. School culture centers around achievement, and a numerical end result rather than the PROCESS of learning and of ENJOYING the learning. It continues as grad schools post minimum averages for admission, where GPA counts - not the student’s ability to critically think, nor their inherent skills in research, independent thought, and educational maturity, but the number at the end of the year which supposedly sums up their worth. As a result, we see grade inflation, a challenge to quality educational assessment. James Côté, a Full Professor in the Department of Sociology at The University of Western Ontario and co-author of Ivory Tower Blues: A University System in Crisis, indicates here, that “The grades of Ontario high school graduates began to increase with the end of standardized exams in the late 60s. By the early 80s, 40% of those applying to universities had A averages. Currently, more than 60% do … Likewise, universities have given increasingly higher grades over the same time period. At what point will we need to adjust the scale in order to actually differentiate among all the A students? In this article, it is discussed that a C no longer represents “average”, as it used to. This cartoon has been suggested as one reason (Source: http://adjunctassistance.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/SeeTheProblem.jpg ), though I think the problem is not that parents are backing up their childrens’ failures to get an A…I think that in both cases, the focus is on someone yelling, complaining, and making someone else feel bad, rather than a discussion that acknowledges a problem and aims to collaboratively work towards a solution. It doesn’t help – it makes everyone on edge, and the problem grows. It shouldn’t be about blame – it should be about how to work together towards a greater good. Moreso, such problems lead to blog posts like this, where millennials are called cry-babies, and this, sarcastically imploring students to shut their mouths, stop whining, and just do their work. Psychology Today, in a more informative than opinionated manner, includes a great article on declining student resilience and increased emotional fragility. What are we to do? Give up educational standards to match the emotional health needs of students? It’s suggested here that we won’t “eliminate the grade-grubbing until we change our current educational system.” However, the same article insists that unless students can educate themselves on this system, they will deprive themselves of real skills and knowledge that prepare them for real success – that what goes on in the classroom will constitute achievement well beyond a grade at the end of it. So, we have a system where students are stressed, and it causes whining about final grades which contributes to the stress of faculty and causes a stress multiplier effect across campus. How can we fix the problem? Is changing the system even a possibility? I think that the lens we use here is critical, and that decreasing stress and building relationships is key to understanding and mutual respect, and in my experience, leads to deeper learning and increased responsibility. Here’s what I want my students to know, and how I want to contribute to all this in my own classroom: Impressing me is easier than you think. If you show up on time, regularly contribute to class discussion, ask thoughtful questions to guide your own learning and complete all your assignments on time showing your thinking, not just regurgitation of facts from the text and slides, I will be impressed. If you talk to me, face to face, in class or out, I will be impressed. The grading system isn’t necessarily fair – there are high grades available for those who are test-wise and have good explicit memories. It doesn’t always represent hard work, application, and critical thinking. I develop assessments that are more akin to measuring some of these characteristics, and those of you who are used to getting top marks for being test-wise and having good memories will get upset when you get a lower grade than expected. That said, those of you who are great critical thinkers, able to apply theory to the real world will be pleasantly surprised that your skills are recognized. That said, down the road, employers will not be asking you what grade you got in my class. I want you to enjoy my class, become inspired by the content, and to learn for the sake of learning, not the sake of the final grade. I want you to be happy. Being stressed about numbers will impede your learning. I don’t want that. I want you to come see me during office hours. I want you to talk to me in class. Talk to me about what is working for you and what isn’t. Tell me what you love about the class and what you just don’t get. Talking to your friends about that doesn’t help me to help you. Getting to know you helps me because then I can be on your side and help you throughout the course. Our relationship matters. And not just for the obvious external reasons, like asking for letters of reference, connections to the network of people I am connected to in your field, potential extensions in special circumstances, or discussions about grades. None of those works well for you if we don’t have a good teacher-student relationship, of course – it’s real-life networking. Even more important than this, though, is that if we have a good relationship, I will understand your stress and help you work through it. I will understand your learning and adjust my approach to maximize student learning. I will ensure that I give you the best education that is personalized to your learning needs as I can. If we don’t have a good relationship, your end of semester grade questions may be perceived as challenges or last minute scrambles as opposed to your responsible and proactive concern for your education. If we don’t have a good relationship, my comments may be misperceived by YOU from time to time, and that might upset you, which is the last thing I want to do. I do this job to make my students happy and to inspire them to become lifelong learners. It’s literally why I do what I do, so please, let me help you to succeed! That is why all my course syllabi state directly that I want to hear from each of you throughout the semester, and I want to hear about your challenges well ahead of assignment due dates. If I don’t, I cannot help you. I have been told by colleagues that they are surprised by how much of my own time and effort I give to individual students. I do – the ones who come to see me. I will not hold your hand and chase you down. I don’t accept assignments that are late. Not even with a penalty. I just don’t accept them. If you can’t plan and get it done, respecting my classroom and your peers, then I will not adjust my own schedule to mark your paper at your convenience. There are firm deadlines in the real world with real consequences – this is just the beginning. I mark in such a way that you know where you can improve as you move through your academic and professional careers, including formative feedback, not just a grade. Don’t ever ask me where you lost marks. No one ever loses marks in my classes. You only earn them. You start my class with a zero, and you work your way up. If you started with 100, there would be no reason for you to keep coming to class. If you want to know how you can improve, come see me. Those are the fair and practical boundaries. BUT, if you are having difficulty with something – anything – and come to talk to me BEFORE any due dates. I won’t help you because you failed to plan, but I will help you to plan, and I can and will adjust accordingly. I will work with you in exceptional ways to ensure a fair way for you to do well in my course. That might mean pre-arranged adjustments to your due dates, alternate assessment opportunities, individual academic support, or help managing difficult situations. If you need anything, talk to me, put an effort in, and you WILL be successful – I am always here for you. Each of you. The take home message is this. You are stressed. I am stressed (especially when I worry about your stress). In each other’s presence, our stress can either multiply, or we can connect to reduce each other’s stress. I want to help you because I want you to be happy. When you are happy, I am less stressed. When I am happy, I can better help you to be less stressed. Please know that I am compassionately here for every single one of you. Talk to me.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorCasey Burgess has a B.Sc.in Psychology, an M.A. in Education (Curriculum and Instruction), and a Ph.D. in progress in Education (Cognition and Learning). She has 20 years experience with direct service, curriculum development, workshop facilitation, and supervisory experience supporting children who have Autism Spectrum Disorders, and their families. She currently frames her work using a developmental, relationship-based, self-regulation lens. Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed